Multi-Armed Bandits and the Exploration–Exploitation Trade-off

If you have been around modern LLMs, you have probably heard of reinforcement learning. At its core, RL is an interaction loop: a learner chooses an action, receives feedback from the environment (reward), updates its rule for acting next time, and repeats. Much of today’s LLM finetuning to align with human preferences can be seen through this lens.

Unlike representation learning where the learner tries to "imitate" the data, RL forces the learner to interact with the environment. The central question in this interaction is how to balance exploration and exploitation. Should the learner take advantage of current knowledge and exploit the option that currently looks best to maximize immediate reward? Or should it take some risks to explore, potentially sacrificing short-term gains to improve knowledge and long-term performance? Too much greed misses better options; too much exploration wastes opportunities.

This fundamental tension between exploration and exploitation appears everywhere in sequential decision-making. Multi-armed bandits capture this trade-off in its simplest form: a single-state Markov decision process focused only on action selection under uncertainty. We now see applications of bandits across industries where information arrives in sequential manner. Examples range from ad placement, recommender systems, packet routing, to more theoretical settings like convex optimization and Brownian motion.

But what are bandit problems exactly?

A key early motivation came from clinical trials. William R. Thompson, in his 1933 paper, proposed assigning treatments adaptively using accumulating evidence, favoring promising options while still testing alternatives enough to learn.

The name “multi-armed bandit” came later. In the 1950s, Mosteller and Bush studied learning in animals and humans. Mice faced left/right choices in a T-shaped maze with uncertain rewards. For humans, they built a two-armed machine: each lever paid out randomly with unknown probabilities. The setup echoed the “one-armed bandit” slot machine, and the term “two-armed,” then “multi-armed,” bandit stuck.

A Classic Dilemma

Imagine you're playing a three-armed bandit machine. You've already pulled each lever several times and observed these payoffs (in dollars):

| Round | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Arm 1 | $5 | - | $5 | - | $5 | - |

| Arm 2 | - | $0 | - | $0 | - | - |

| Arm 3 | - | - | $15 | - | - | $0 |

So far, Arm 1 averages $5, Arm 2 averages $0, and Arm 3 averages $7.50. You have 10 more pulls remaining. Do you stick with Arm 1 (reliable $5), gamble on Arm 3 (high variance but higher average), or give Arm 2 another chance? How do you balance exploiting what seems best versus exploring to learn more?

This illustrates the core dilemma in bandit problems: balancing exploration (trying uncertain options to gather information) and exploitation (using the currently best-performing option to maximize immediate reward).

The Regret and Finite-Armed Stochastic Bandits

Bandit theory can quickly become intimidating as you could dive arbitrarily deep into measure theory, σ-algebras, or martingales. But that isn't necessary to grasp the core ideas. Instead, let's build intuition with the simplest meaningful setting: finite-armed stochastic bandits. This framework captures the essence of exploration versus exploitation while remaining concrete enough to analyze common solution strategies.

The problem statement is as follows: we have $K$ arms, where pulling arm $i$ at time $t$ yields reward $X_{i,t}$ drawn from an unknown distribution $\nu_i$ with mean $\mu_i$. The learner's goal is to minimize regret after $n$ rounds, which is the difference between the cumulative reward achieved by the learner, and that of an oracle that always pulls the optimal arm.

Why not evaluate a learner by raw cumulative reward $\sum_{t=1}^n X_t$?

- It is random: comparing policies requires a utility for the distribution of $S_n = \sum_{t=1}^n X_t$.

- The instance is unknown: a policy that maximizes $\mathbb{E}[S_n]$ for one set of rewards may perform poorly on another.

Regret avoids both by comparing the learner to an oracle that always pulls the best arm.

Define the optimal arm as $i^* = \arg\max_{i \in [K]} \mu_i$ with optimal mean $\mu^* = \mu_{i^*}$. The gap for arm $i$ is $\Delta_i = \mu^* - \mu_i$. After $n$ rounds, the cumulative regret is:

$$R_n = n\mu^* - \mathbb{E}\!\left[\sum_{t=1}^n X_{I_t, t}\right]$$

where $I_t$ is the arm selected at time $t$. Minimizing regret is equivalent to maximizing expected reward, but regret normalizes performance relative to the (unknown) optimum. If rewards were known, always pulling $i^*$ would give $R_n=0$.

Let $\Delta_i = \mu^* - \mu_i$ and let $N_i(n) = \sum_{t=1}^n \mathbb{1}_{\{I_t = i\}}$ be the (random) number of pulls of arm $i$ by round $n$. Then we have the regret decomposition:

$$R_n = \sum_{i=1}^K \Delta_i\, \mathbb{E}[N_i(n)]$$

This identity exposes the exploration–exploitation trade-off: each pull of a suboptimal arm incurs $\Delta_i$ expected loss. Good algorithms keep $\mathbb{E}[N_i(n)]$ small for large gaps while still exploring when gaps are small, targeting sublinear regret $R_n = o(n)$. The decomposition also provides a powerful framework for algorithm analysis. Instead of directly bounding the complex random quantity $R_n$, we can analyze each $\mathbb{E}[N_i(n)]$ separately.

Now let's formalize the problem setup.

Problem Setup

- $K$ arms with unknown reward distributions $\nu_1, \ldots, \nu_K$

- At round $t$, learner selects arm $I_t$ and receives reward $X_{I_t,t} \sim \nu_{I_t}$

- Arm $i$ has mean reward $\mu_i = \mathbb{E}[\nu_i]$

- Optimal arm: $i^* = \arg\max_i \mu_i$, gap: $\Delta_i = \mu^* - \mu_i$

- Assumption: rewards are $\sigma$-subgaussian

- Goal: Minimize regret $R_n = n\mu^* - \mathbb{E}[\sum_{t=1}^n X_{I_t,t}]$

Concentration Inequalities

Before analyzing bandit algorithms, we need one more tool from probability theory: concentration of measure. The core challenge of the bandit problem is that the optimal action has the largest mean reward, but these means are initially unknown and must be learned from observations. This raises a fundamental question: how confidently can we estimate the mean of an action from a finite number of samples?

To answer this, we study tail probabilities: the probability that our empirical estimate deviates significantly from the true mean. Tight bounds on these probabilities let us construct confidence intervals, ranges within which the true mean lies with high probability. The tighter these intervals, the more efficiently we can balance exploration and exploitation.

We begin with two classical inequalities that provide our first handle on tail probabilities.

Markov's Inequality: For any non-negative random variable $X$ and $\varepsilon > 0$,

$$\mathbb{P}(X \geq \varepsilon) \leq \frac{\mathbb{E}[X]}{\varepsilon}.$$

Chebyshev's Inequality: For any random variable $X$ with finite variance,

$$\mathbb{P}\left(|X - \mathbb{E}[X]| \geq \varepsilon\right) \leq \frac{\mathbb{V}[X]}{\varepsilon^2}.$$

To see Chebyshev's limitations, apply it to a sample mean $\hat{\mu}_n = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n X_i$ where each $X_i$ has variance $\sigma^2$. Since $\mathbb{V}[\hat{\mu}_n] = \sigma^2/n$,

$$\mathbb{P}(|\hat{\mu}_n - \mu| \geq \varepsilon) \leq \frac{\sigma^2}{n\varepsilon^2}.$$

This bound exhibits polynomial decay in both parameters $\varepsilon$ and $n$. Chebyshev's and Markov's inequalities are nice because they make no assumptions about the distribution of $X$, and only rely on the existence of the mean and variance. However, when $X$ has well-behaved tails (like Gaussian or bounded random variables), they are a bit too loose. And to get failure probability $\delta$, we need $n = \Omega(\sigma^2/(\varepsilon^2\delta))$ samples, linearly in $1/\delta$.

To obtain exponentially decaying tail bounds, we introduce the notion of subgaussian random variables. A random variable $X$ with $\mathbb{E}[X] = 0$ is called $\sigma$-subgaussian if its moment generating function satisfies

$$\mathbb{E}[\exp(\lambda X)] \leq \exp\left(\frac{\lambda^2 \sigma^2}{2}\right) \quad \text{for all } \lambda \in \mathbb{R}.$$

Intuitively, this says that $X$ has tails no heavier than a Gaussian with variance $\sigma^2$. Bounded random variables, Gaussian random variables, and many other common distributions satisfy this property. The power of subgaussianity lies in the following fact:

If $X$ is $\sigma$-subgaussian with $\mathbb{E}[X] = 0$, then for any $\varepsilon \geq 0$,

$$\mathbb{P}(X \geq \varepsilon) \leq \exp\left(-\frac{\varepsilon^2}{2\sigma^2}\right).$$

The real power appears when we apply this to sample means. For $\hat{\mu}_n = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n X_i$ with each $X_i$ being $\sigma$-subgaussian with mean $\mu$, we get a much tighter bound:

$$\mathbb{P}(|\hat{\mu}_n - \mu| \geq \varepsilon) \leq 2\exp\left(-\frac{n\varepsilon^2}{2\sigma^2}\right).$$

Subgaussian random variables have convenient closure properties that make them easy to work with in practice.

Properties of Subgaussian Random Variables

Suppose $X$ is $\sigma$-subgaussian with $\mathbb{E}[X] = 0$, and $X_1, X_2$ are independent and $\sigma_1$- and $\sigma_2$-subgaussian, respectively. Then:

- $\mathbb{E}[X] = 0$ and $\mathbb{V}[X] \leq \sigma^2$

- For any constant $c \in \mathbb{R}$, $cX$ is $|c|\sigma$-subgaussian

- $X_1 + X_2$ is $\sqrt{\sigma_1^2 + \sigma_2^2}$-subgaussian

These properties immediately give us concentration bounds for sample means, which are the building blocks of bandit algorithms.

Let $X_1, \ldots, X_n$ be independent, $\sigma$-subgaussian random variables with mean $\mu$. Let $\hat{\mu} = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n X_i$. Then for any $\varepsilon \geq 0$,

$$\mathbb{P}(\hat{\mu} \geq \mu + \varepsilon) \leq \exp\left(-\frac{n\varepsilon^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \quad \text{and} \quad \mathbb{P}(\hat{\mu} \leq \mu - \varepsilon) \leq \exp\left(-\frac{n\varepsilon^2}{2\sigma^2}\right).$$

Inverting the bound: setting $2\exp(-n\varepsilon^2/(2\sigma^2)) = \delta$ and solving for $\varepsilon$, we get that after $n$ samples, with probability at least $1 - \delta$,

$$\mu \in \left[\hat{\mu}_n - \sqrt{\frac{2\sigma^2\log(2/\delta)}{n}}, \; \hat{\mu}_n + \sqrt{\frac{2\sigma^2\log(2/\delta)}{n}}\right].$$

This confidence interval is the foundation of the UCB algorithm. The width shrinks as $1/\sqrt{n}$. We will see the powerful implications of this bound in the next section.

Explore-then-Commit

Before diving into principled algorithms, consider these simple heuristics:

- Greedy: Always play the arm with the highest empirical mean. This can get stuck on a suboptimal arm due to lack of exploration, leading to linear regret.

- Uniform exploration: Play all arms an equal number of times. This is pure exploration with no exploitation, also yielding linear regret.

- ε-greedy: With probability $1-\epsilon$, exploit by playing the empirically best arm; with probability $\epsilon$, explore by playing a random arm. This achieves $O(\log n)$ regret with proper tuning.

While ε-greedy can work reasonably well, it explores uniformly without considering confidence in the estimates. This motivates more sophisticated approaches.

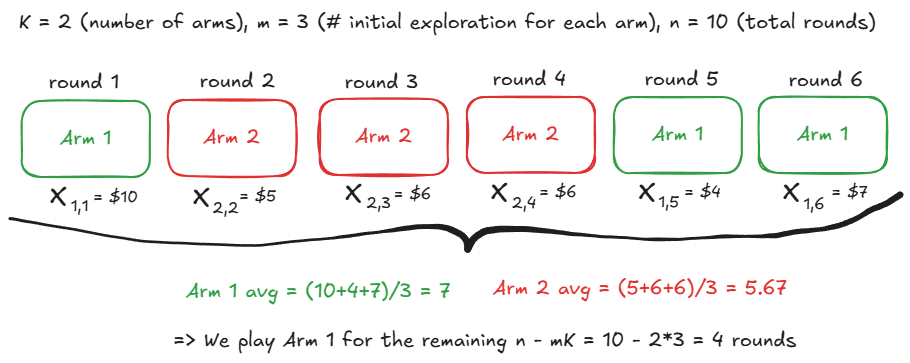

The first principled method we explore is called Explore-then-Commit. The approach is, explore each action/arm a fixed number of times ($m$), then exploit the knowledge by choosing the arm with the largest empirical payoff.

Explore-then-Commit Algorithm

- Explore phase: Pull each arm exactly $m$ times

- Compute empirical means: $\hat{\mu}_i = \frac{1}{m}\sum_{j=1}^m X_{i,j}$ for each arm $i$

- Commit phase: Select $\hat{i} = \arg\max_i \hat{\mu}_i$ and pull it for all remaining $n - mK$ rounds

To analyze the regret of ETC, recall that $R_n = \sum_{i=1}^K \Delta_i \mathbb{E}[N_i(n)]$ from the regret decomposition above. Let's denote $i^* = \arg\max_i \mu_i$ as the optimal arm.

Theorem (ETC Regret Bound)

$$R_n \leq m \sum_{i=1}^K \Delta_i + (n - mK) \sum_{i=1}^K \Delta_i \exp\left(-\frac{m\Delta_i^2}{4}\right)$$

Intuitively, this bound captures the exploration–exploitation balance. Choosing a large $m$ means more time sampling every arm, so the first term (proportional to $m$) grows. Picking $m$ too small raises the chance of committing to a suboptimal arm, inflating the second term, which decreases only when $m$ is large enough to make the misidentification probability tiny.

Proof: In the first $mK$ rounds, the policy is deterministic, choosing each action exactly $m$ times. Subsequently it chooses a single action maximizing the average reward during exploration. Thus,

$$\mathbb{E}[N_i(n)] = m + (n - mK)\mathbb{P}(I_{mK+1} = i) \tag{1}$$

$$\leq m + (n - mK)\mathbb{P}\left(\hat{\mu}_i(mK) \geq \max_{j \neq i} \hat{\mu}_j(mK)\right)$$

The probability on the right-hand side is bounded by:

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbb{P}\left(\hat{\mu}_i(mK) \geq \max_{j \neq i} \hat{\mu}_j(mK)\right) &\leq \mathbb{P}(\hat{\mu}_i(mK) \geq \hat{\mu}_{i^*}(mK)) \\ &= \mathbb{P}(\hat{\mu}_i(mK) - \mu_i - (\hat{\mu}_{i^*}(mK) - \mu_{i^*}) \geq \Delta_i) \end{aligned}$$

Then, we can show that $\hat{\mu}_i(mK) - \mu_i - (\hat{\mu}_{i^*}(mK) - \mu_{i^*})$ is $\sqrt{2/m}$-subgaussian, which follows from standard subgaussian properties. Hence by Hoeffding's inequality:

$$\mathbb{P}(\hat{\mu}_i(mK) - \mu_i - \hat{\mu}_{i^*}(mK) + \mu_{i^*} \geq \Delta_i) \leq \exp\left(-\frac{m\Delta_i^2}{4}\right)$$

Substituting this into (1) gives:

$$\mathbb{E}[N_i(n)] \leq m + (n - mK)\exp\left(-\frac{m\Delta_i^2}{4}\right)$$

Using the regret decomposition $R_n = \sum_{i=1}^K \Delta_i \mathbb{E}[N_i(n)]$ yields the regret bound stated above.

To choose the right $m$, we simplify to the basic two-arm instance: arm 1 is optimal ($\Delta_1=0$) and arm 2 is suboptimal with gap $\Delta_2=\Delta$. Then $K=2$ and the bound becomes $$R_n \;\le\; m\,\Delta + (n-2m)\,\Delta\,\exp\!\left(-\tfrac{m\Delta^2}{4}\right) \;\le\; m\,\Delta + n\,\Delta\,\exp\!\left(-\tfrac{m\Delta^2}{4}\right)$$

The optimal choice is $m = \max\left\{1, \left\lceil \frac{4}{\Delta^2} \log\!\left(\frac{n\Delta^2}{4}\right) \right\rceil \right\}$ for gap $\Delta$. For the worst-case over gaps, this gives:

$$R_n \leq \Delta + C\sqrt{n}$$

where $C > 0$ is a universal constant. When $\Delta \leq 1$, we get $R_n \leq 1 + C\sqrt{n}$, or simply $R_n = O(\sqrt{n})$.

The previous choice of $m$ is close to the optimal choice, but it depends on both the unknown gap $\Delta$ and time horizon $n$. A standard alternative is to pick $m$ as a function of horizon $n$ only. For two 1-subgaussian arms, this yields a gap-free bound:

$R_n = O(n^{2/3})$

Upper Confidence Bound (UCB)

UCB elegantly addresses ETC's limitations by adaptively balancing exploration and exploitation. Instead of rigid phases, UCB constructs confidence intervals around arm means and selects the arm with highest upper confidence bound, a principle which we call optimism under uncertainty.

At time $t$, having selected arm $i$ a total of $N_i(t-1)$ times and observed empirical mean $\hat{\mu}_i(t-1)$, UCB selects:

$$I_t = \arg\max_{i \in [K]} \left( \hat{\mu}_i(t-1) + \sqrt{\frac{2\log (1/\delta)}{N_i(t-1)}} \right)$$

The term $\hat{\mu}_i(t-1)$ is the exploitation component, favoring arms that have produced large average rewards so far. The square-root term is the exploration bonus (confidence width): it is larger for arms with few samples ($N_i(t-1)$ small) and decreases as $1/\sqrt{N_i(t-1)}$, encouraging additional pulls until the estimate is accurate.

The expression inside the argmax is called the index of arm $i$. Index algorithms form a broad class of bandit strategies where each arm is assigned a numerical score (the index) based on its historical performance and uncertainty. The algorithm then simply selects the arm with the highest index at each round. Intuitively, this leads to sublinear regret because when the optimal arm's index overestimates its true mean, any suboptimal arm must achieve an index value exceeding the optimal arm's index to be selected. However, this can't happen too often as the learner continues to explore the environment and update its estimates.

The UCB algorithm is defined as follows:

UCB Algorithm

Input: Confidence parameter $\delta \in (0,1)$

Initialization: Pull each arm once

For rounds $t = K+1, K+2, \ldots, n$:

- Compute UCB for each arm: $\mathrm{UCB}_i(t, \delta) = \hat{\mu}_i(t-1) + \sqrt{\frac{2\log (1/\delta)}{N_i(t-1)}}$

- Select arm: $I_t = \arg\max_i \mathrm{UCB}_i(t, \delta)$

- Observe reward and update estimates

Without loss of generality, let arm 1 be optimal with mean $\mu_1=\mu^*$, analysis for the regret after $n$ rounds can start by writing regret decomposition:

$$R_n \,=\, \sum_{i=1}^K \Delta_i\,\mathbb{E}[N_i(n)],\qquad \Delta_i = \mu_1 - \mu_i.$$

Then, we can bound $\mathbb{E}[N_i(n)]$ for every suboptimal arm $i\neq 1$. We observe afer the initial period where UCB pulls each arm once, suboptimal arm $i$ can only be selected at time $t$ only if its index exceeds that of the optimal arm.

For this to happen, at least one of the following two events occur:

(a) The index of action $i$ is larger than the true mean of a specific optimal arm.

(b) The index of a specific optimal arm is smaller than its true mean.

To formalize this, we introduce the good event $G_i$ for each suboptimal arm $i \neq 1$, which captures the scenario where all confidence intervals behave as intended.

$$G_i = \left\{ \min_{t \in [n]} \mathrm{UCB}_1(t, \delta) > \mu_1 \right\} \cap \left\{ \hat{\mu}_{i, u_i} + \sqrt{\frac{2}{u_i} \log(1/\delta)} < \mu_1 \right\}$$

Here, $u_i$ is a threshold number of pulls for arm $i$ (to be chosen later), and $\delta$ is a small probability parameter. The first condition ensures that the optimal arm's index never dips below its true mean during the entire horizon, while the second guarantees that after $u_i$ samples, the index for arm $i$ falls below $\mu_1$ forever after. The crux of the regret bound is to show two things:

- If $G_i$ holds, arm $i$ is played at most $u_i$ times, in other words, $T_i(n) \leq u_i$.

- The probability $\mathbb{P}(G_i^c)$ is small.

Combining these two results, decompose the expected number of pulls by conditioning on whether $G_i$ occurs:

$$\mathbb{E}[T_i(n)] = \mathbb{E}[\mathbb{1}\{G_i\} T_i(n)] + \mathbb{E}[\mathbb{1}\{G_i^c\} T_i(n)] \leq u_i + \mathbb{P}(G_i^c) \cdot n,$$

where we used $T_i(n) \leq u_i$ on event $G_i$, and $T_i(n) \leq n$ always holds (since we cannot pull more than $n$ times total).

With $\delta = 1/n^2$ and choosing $c = 1/2$, we obtain from the bound above

$$\mathbb{E}[T_i(n)] \leq u_i + 1 + n^{1-2c^2/(1-c)^2} = \left\lceil \frac{8\log(n^2)}{(1-1/2)^2\Delta_i^2} \right\rceil + 1 + n^{-1} \leq 3 + \frac{16\log(n)}{\Delta_i^2}.$$

Using the regret decomposition $R_n = \sum_{i=1}^K \Delta_i \mathbb{E}[T_i(n)]$, we get the instance-dependent bound:

$$R_n \leq \sum_{i:\Delta_i>0} \Delta_i \left( 3 + \frac{16\log(n)}{\Delta_i^2} \right) = 3\sum_{i:\Delta_i>0}\Delta_i + \sum_{i:\Delta_i>0} \frac{16\log(n)}{\Delta_i}.$$

For the gap-free bound, we partition arms into those with small gaps ($\Delta_i < \Delta$) and large gaps ($\Delta_i \geq \Delta$) for a threshold $\Delta$ to be chosen, and obtain:

$$R_n \leq 8\sqrt{kn\log(n)} + O(1)$$

Interactive Comparison: ETC vs UCB

Explore-then-Commit

Upper Confidence Bound

Cumulative Regret Comparison

References

- Lattimore, T., & Szepesvári, C. (2020). Bandit Algorithms. Cambridge University Press.